Mid Century Architects

Top 10 Most Renowned Mid Century Modern Architects

Scores of professionals can be considered icons of Mid Century Modern architecture. The 10 listed here are considered the most influential. While a few are officially from other “schools,” (International, Bauhaus, Prairie), all of these architects share the same devotion to the Mid Century Modern principles : function takes priority over form, buildings are integrated into their environment, open spaces dominate, simplicity in all things, and the middle classes deserve beauty and integrity in their surroundings.

of European Modernism.

Walter Gropius (1883 – 1969)- This German national is credited with being one of the founders of European Modernism. After studying architecture for just four semesters in the early 1900s, he began work with an industrial designer, rather than a more artistic creative. Of course, industrial designers focus more on how their creations fulfill a business’s purpose. This approach helped shape Gropius’s drive to prioritize function over form.

A third generation architect, Gropius opened his own practice in 1910 with a partner. His 1913 article “The Development of Industrial Buildings” won him respect and even renown among his peers. He designed factories and a train engine before serving as a lieutenant in the signal corps during World War I.

In 1919, Gropius was appointed master of the Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts, where he emphasized the functional design model. This school soon became known as The Bauhaus School and was set in contrast to the Ecole of Beaux Arts in Paris, an institution devoted to traditional, Greco-Roman, massive and ornate style. Gropius emphasized the importance of providing beautiful, high-quality architecture and design to those outside the upper classes, another tenet of Mid Century Modernism. With material prices plummeting due to the advances during the Industrial Revolution, Gropius believed this goal a worthy one.

Recognizing the growing power of Fascism, Gropius escaped Germany in 1934 to live in Britain. He then relocated to Massachusetts where he built a simple, economical home with the “new” materials. Now known as “Gropius House,” this home is owned by Historic New England and designated as National Historic Landmark.

Gropius’s most honored buildings include the J.F. Kennedy Federal Building, The PanAm Building and the Fagus Factory.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886 – 1969) – While van der Rohe began his career designing in the neoclassical style that was popular during the time, he grew increasingly convinced by detractors that Victorian, Georgian, Baroque and more styles were over-ornamented, overdone and too fawning of the an aristocratic social structure that needed to end.

A contemporary of Walter Gropius, van der Rohe called his buildings “skin and bones” architecture to reflect their simplicity. His modernist debut occurred in 1921 when he won the contract to build the faceted, all-glass Friedrichstraße skyscraper. His German Pavilion for the Barcelona Exposition and the Villa Tugendhat in the Czech Republic.

Ludwig Meis van der Rohe accepted colleague Walter Gropius’s plea to take over as director of the Bauhaus, but by 1933, the great depression and other forces decimated the number of architectural commissions and the school closed. In 1937, with little work in Europe, van der Rohe welcomed an offer to head the department of architecture at the new Illinois Institute of Technology. His modern approach eventually became known as the Second Chicago School.

Experts consider Chicago’s Crown Hall to be van der Rohe’s masterpiece. In his work in the United States, he also completed the Farnsworth House, the Seagram Building, and Chicago Federal Complex.

The architect’s complex last name prompted those in the industry to use his first name—Mies—to define his style: Miesian.

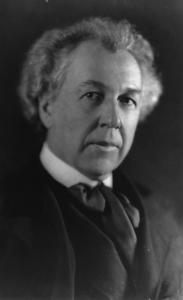

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867 – 1959) – Still America’s most renowned architect, Frank Lloyd Wright began as a draftsman and construction supervisor by leveraging family contacts.

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867 – 1959) – Still America’s most renowned architect, Frank Lloyd Wright began as a draftsman and construction supervisor by leveraging family contacts.

He learned much about architecture in his first job at the firm Joseph Lyman Silsbee, but longed for new design as opposed to the Victorian and Revivalist styles the firm was rehashing. He moved to Adler & Sullivan as Louis Sullivan’s draftsman and spent several years mimicking Sullivan’s design style. Upon his marriage, he asked the firm for some money to design and build his own house.

Finding the heavy, ornamented neo-classical styles “grotesque,” Wright’s home features clean lines, large open spaces and emphasis on natural materials. Just 22 years old when the house was completed, Wright and his wife, Catherine eventually raised six children in the house. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976. Today the home is operated by the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust which gives tours and hosts events.

With a penchant for life’s luxuries (cars, clothing), Wright found himself in need of extra money. He moonlighted designing homes for families in Chicago. When firm owner Louis Sullivan started recognizing Wright’s buildings going up, he claimed Wright was in breach of contract. The two argued and Wright left to start his own firm, eventually landing in Steinway Hall in Chicago where several other forward-thinking architects had set up shop. Together, Wright and these colleagues leveraged the style of Louis Sullivan as well as the burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement. Their common approach became known as “The Prairie School.” With openness, functionality and simplicity at its center, The Prairie School became a progenitor for Mid Century Modernism.

After leaving Alder & Sullivan in 1893, Wright completed 50 projects in the following eight years. To get that much work, he sometimes had to follow client instructions and design the ornamented neo-classical monstrosities he rejected. He worked his own, simpler, sweeping-line designs in where he could.

Wright’s residential designs of this era were known as “prairie houses” because the designs complement Illinois wide, flat and grassy terrain. Wright kept the homes to two-stories (where traditional homes could be three or more) with one-story projections. Shunning walls dividing up the first floor interior, he opened kitchen to living room to dining room as much as he could. The low-pitched roofs ended in broad overhanging eaves. He showcased the beauty of wood, brick and other natural materials and opened home interiors up to the outdoors with big windows.

While historians consider Fallingwater in Pennsylvania (below) to be Wright’s masterpiece, other residences like the Arthur Heurtley House and Darwin Martin House are both considered showpieces.

Wright’s most lauded commercial works include Oklahoma’s Price Tower, the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, and the Johnson Wax headquarters in Wisconsin.

Throughout a chaotic personal life impacted by scandal (3 partners/wives, one murdered by a mentally ill employee, and 7 children), Wright completed 425 buildings.

Marion Mahoney (1871 – 1961) – one of the first licensed female architects in the world made a mark that wasn’t always recognized. From a creative family, Mahoney was inspired by an older cousin who became an architect. She struggled with her role in society, but clearly talented, she responded to encouragement from professors and others to complete her bachelor’s degree and become a professional architect.

Mahoney met Frank Lloyd Wright while working in her first job in her cousin’s architecture firm which happened to be in the Steinway Hall, a hub for forward-thinking architects at the time. Her watercolor, drawing and other artistic abilities got Wright’s attention, and he hired her as his first employee. Unfortunately, Wright took credit for Mahoney’s beautiful watercolor renderings of buildings and landscapes.

Mahoney’s hesitance to lead an architecture firm in her own right came to the fore when in 1909 Frank Lloyd Wright eloped to Europe with Mamah Borthwick Cheney who would become his second wife. Wright offered his current work to Mahoney, but she declined. Another architect took over Wright’s projects, hiring Mahoney on and giving her design control. The two finished several projects together.

Partnering with Walter Griffin, Mahoney designed the Rock Crest – Rock Glen development in Mason City, Iowa. The development is the largest collection of Prairie Style homes surrounding a natural environment. It’s considered their best American work. Mahoney married Walter Griffin and they remained together for 26 years until his death in 1937. The pair worked together to design Australia’s new capital, Canberry.

Today, architectural historians credit Marion Mahoney for helping to develop and expand the American Prairie School.

Richard Neutra (1892 – 1970) – 30 years younger than Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra began studying architecture and design after modernism had gotten a solid foothold in Europe. His studies were interrupted by World War I, where he served as a lieutenant in the Balkans artillery until 1917.

After working six years for German firms, he migrated to the United States in 1923 to work with Frank Lloyd Wright. A proponent of European “Internationalism,” the modern architecture movement there, Neutra and Wright collaborated on several projects. Soon, however, Neutra accepted an invitation from his university friend, Rudolph Schindler to join a practice in Los Angeles, California. There, Neutra designed elements of the now renowned Schlinder – Chace House or King’s Road house now run under the non-profit MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

In 1929, however, Neutra split from his friend to establish his own firm. He designed scores of homes and commercial buildings, 12 of which became Historical Cultural Monuments in the National Historic Register, including the Lovell House, pictured here.

In 1932, his work was included in a seminal MoMA modern art exhibition, cementing his influence. His firm continued to grow, and in 1955 he won the commission to design the U.S. embassy in Karachi.

Known for his watercolors and drawings, Neutra, like Marion Mahoney was able to beautifully render his architectural visions. His California homes and buildings maintained allegiance to geometric shape, but he opened up floor plans even more than Wright and the Steinway Hall crowd in Chicago.

Neutra died in 1970. His son Dion Neutra, also an architect, still works out of the Silver Lakes office the two opened in 1965.

Rudolf Schindler (1887 – 1953) – a classmate of Richard Neutra at the Vienna Institute of Technology, Schindler managed to escape Europe before being conscripted by the army as his friend had.

In 1911, Schindler made it to Chicago, then the center of architecture. During his three years work at a firm in the city, he was writing letters to Frank Lloyd Wright. The two finally met in 1914, but Wright was still reeling from the murder of his mistress (Mamah Borthwick Cheney) and arson of his home, Taliesin, perpetrated by a mentally ill employee.

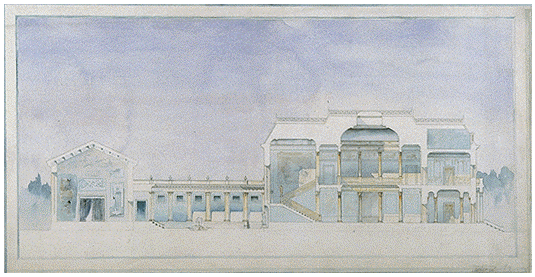

A few years later, Wright won the commission to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo and hired Schindler to run his American operations. When, for years, Wright refused to give Schindler the credit for designs and drawings SchliSchindlerder believed he deserved, the two split in 1931. Schindler opened his own practice in Los Angeles, where he started The King’s Road House or Schindler-Chace House, one of his most well-known structures.

Schindler first favorite material was concrete, but wanting to reduce the cost of his buildings, switched to plaster. Despite the architect’s inventiveness, he was snubbed at the first International Architecture show, in which his friend, Richard Neutra appeared. Still, six of his buildings are now City of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments and appear in the National Historic Register.

Schlinder – Chace House

Eero Saarinen (1910 – 1961) – Son of a prominent architect, Eero Saarinen finished his architecture studies at the Yale School of Architecture in 1934, around the time Rudolf Schindler’s work with Frank Lloyd Wright was ending.

Technically considered a “neo-futurist,” Saarinen incorporated many of the tenets of mid-century modernism in his furniture design and architecture work. He worked with Charles and Ray Eames on the now perennially popular Eames chair. His buildings have the simple, often curved lines, and open spaces. Neo-futurism, like Mid Century Modernism, strove toward a style that reflected a belief in a better future and the promise of technology.

His commercial work includes the TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport in New York City, the St. Louis Arch, the U.S. Embassy in London, the Brandeis University campus and many more.

Sarrinen’s TWA Center at JFK Airport in New York

Florence Knoll (1917 – 2019) – A protege of Mies van der Rohe and Eero Saarinen’s father Eliel Saarinen, Florence Knoll advanced Mid Century Modern furniture design and architecture, particularly for commercial structures.

After studying with them at Cranbrook Academy of the Arts, she moved to Massachusetts to work with Walter Gropius (above), one of the very first architects to promote practical Mid Century Modern style. Her most famous works include the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company Headquarters and the interior of the CBS building in New York.

Connecticut General Life Insurance Company Headquarters

In the early 1940s, artisan furniture maker Hans Knoll caught her eye. She pushed him to align with architects in order to sell more furniture. After marrying in 1946, they formed Knoll Associates, which became a worldwide brand still popular for Mid Century Modern furniture today. Upon his death in 1955, Florence Knoll took over the company and designed the office chairs, tables and other pieces the catalog still carries.

Florence Knoll emphasized clean, uncluttered office spaces with light furniture rather than heavily carpeted rooms with heavy mahogany or oak desks. She created the boat-shaped conference table, designed so all participants could see each other. She also shook up office building interiors with multiple levels and open-riser staircases that seems to float.

Stewart Williams (1909 – 2005) – Son of notable architect Harry Williams who set up shop in Palm Springs after designing its La Plaza Shopping Center. Stewart attended the renowned Cornell School of Architecture then went on to teach at Columbia. In 1938, he joined his father and brother, also an architect, in their firm Williams, Williams & Williams.

Stewart Williams was a prolific architect, best known for talking Frank Sinatra out of building a dated Georgian mansion sitting 4 stories high in the desert. Instead, they built Twin Palms, which set the tone for Mid Century Modern architecture after World War II.

Twin Palms is now available for weddings and other events. Tours go through regularly. Several of Williams’s buildings are now on the National Register of Historic Homes, and he has a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars.

Donald Wexler (1926 – 2015) – Born in Minnesota, Donald Wexler moved to Palm Springs in 1952 and maintained his practice there for 60 years. Using steel for framing, roofs, and even siding, he developed an architecture that worked ideally with the hot, desert climate. In 1964, he build a house for Dinah Shore in Palm Springs. Leonardo DiCaprio bought the residence in 2014 for $5,230,000. Wexler, too, has a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars.